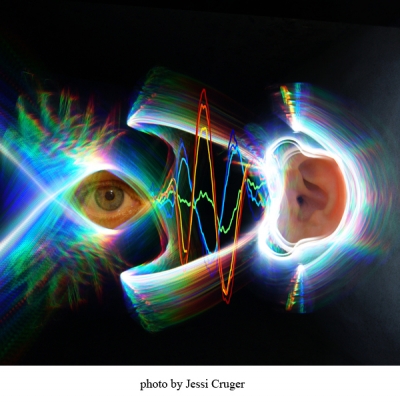

The Eardrums Move When the Eyes Move

Duke Professor of Psychology & Neuroscience Jennifer Groh and a team of researchers have found that simply moving the eyes triggers the eardrums to move too. In a paper published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers found that keeping the head still but shifting the eyes to one side or the other sparks vibrations in the eardrums, even in the absence of any sounds.

"This was really a team effort, instigated by a very determined Kurtis Gruters who received his PhD for this work, and now being continued by David Murphy, a current graduate student in our department of Psychology & Neuroscience," said Groh, the principal investigator. "In addition, we have been fortunate to be working with a very dedicated undergraduate neuroscience student, Cole Jenson, and two stellar collaborators who provided invaluable expertise and guidance in otoacoustic emissions -Christopher Shera from USC and David W. Smith from the University of Florida."

Surprisingly, these eardrum vibrations start slightly before the eyes move, indicating that motion in the ears and the eyes are controlled by the same motor commands deep within the brain. “It’s like the brain is saying, ‘I’m going to move the eyes, I better tell the eardrums too,’” Groh said.

The findings, which were replicated in both humans and rhesus monkeys, provide new insight into how the brain coordinates visual and auditory sensations. It may also lead to new understanding of hearing disorders that don’t result in differences in auditory sensitivity, such as difficulty following a conversation in a crowded room.

It’s no secret that the eyes and ears work together to make sense of the sights and sounds around us. Most people find it easier to understand somebody if they are looking at them and watching their lips move. And in a famous illusion called the McGurk Effect, visual cues from the eyes trick the ears into hearing “fah,” when the actual sound is “bah.” But researchers are still puzzling over where and how the brain combines these two very different types of sensory information.

“Our brains would like to match up what we see and what we hear according to where these stimuli are coming from,” Groh said. “But the visual system and the auditory system figure out where stimuli are located in two completely different ways.”

Though eardrums vibrate primarily in response to outside sounds, the brain can also control their movements using small bones in the middle ear and hair cells in the cochlea, Groh said. This mechanism helps modulate the volume of sounds that ultimately reach the inner ear and brain.

Read study on PNAS website:

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2018/01/22/1717948115

In the Atlantic:

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/01/when-your-eyes-move-so-do-your-eardrums/551237/

Dr. Jennifer Groh Lab:

http://people.duke.edu/~jmgroh/