How One Tweet of Encouragement Can Impact a Career

Duke postdoc Lauren Green wasn’t expecting to make a revolutionary brain cell discovery as a second-year graduate student. But that’s exactly what happened.

“I was really considering leaving science,” Green said.

It wasn’t that Green wanted to quit, but she was plagued by self-doubt, experiencing a common stage for many budding scientists working toward their Ph.D. She felt overwhelmed: greatly invested in her research, TAing, completing qualifying exams, and constantly questioning if she was good enough.

“In science, you get a ton of negative data from your research,” Green said. “There’s a lot more failures than there are wins.”

But a big win did come. In the form of a zebrafish and a tweet.

As a graduate student at Notre Dame University, Green studied zebrafish, an important non-mammal species commonly used in scientific research because of their similar genetic structure to humans and ability to experience equivalent diseases. Green was particularly interested in a very small part of these fish: microglia.

Microglia, also called glia, are a type of immune cell in the brain. They’re like tiny spiders hunting for debris, keeping the brain clean and healthy — but they reside only in the brain.

That was the science. Until Green’s research.

Green observed zebrafish glia day in and day out. She loved the work and was fascinated by the vibrant imagery. “You can actually see the cells move in real time,” she said. “I just love the science.”

Working in the lab of her Notre Dame mentor, Cody Smith, Green’s glia experiments mimicked injuries to the zebrafish. Her work was to monitor how the zebrafish cells responded to damage, in contrast to a normal, healthy state.

One day, as one microglia in the zebrafish was responding — bloop, it popped out of the brain.

It was a revelation.

Green immediately contacted Smith. “Is this normal?,” she asked.

“Holy shit!,” he replied.

Green and Smith watched in awe and proceeded to complete rounds of the same injury. Over time, the data showed the same response 40 percent of the time. Green’s zebrafish study revealed that microglia can crawl out of the brain, migrate to other systems in the body, consume damaged cells, and then crawl back into the brain, changed.

The results were not at all what experts in the glia field thought was possible and it raised all sorts of implications for a similar response in mammals.

Yet many in the field didn’t consent the study’s validity. That was hard for Green to understand. “We had video of it happening, but people still didn’t believe it.”

In 2019, Green presented her findings at a brain science conference in New York, and Duke Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience Staci Bilbo was stunned.

“Microglia are the cells that I study and love very much,” Bilbo said.

After the talk, Bilbo chatted with Green about her research. Later, Green emailed Bilbo, thanking her for showing an interest. A few hours later, Bilbo replied: “It was lovely to meet you as well. Good luck with your paper and let me know when you’re ready for a postdoc.” Followed by a winky-face emoji.

But Bilbo wasn’t being playful — she was blown away by Green. “It was one of the best talks I have ever seen,” Bilbo said. “And by a second-year grad student? Lauren was so well-spoken and self-assured.”

Green recalls that after her talk at the New York conference, several prominent male figures in the field pulled her aside to tell her why her data was wrong.

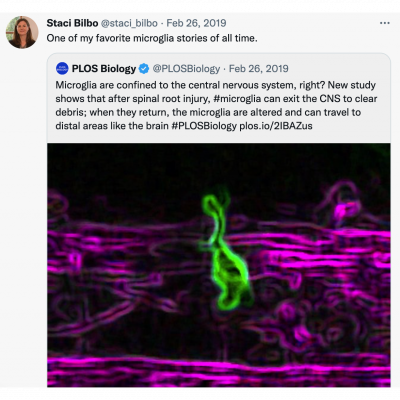

Six months after that conference, and Bilbo and Green’s initial meeting, Green’s research on microglia was published in PLOS Biology.

That very same day, Bilbo tweeted it.

Green’s mentor, Cody Smith, took a screenshot of the tweet and sent it to Green: “You need to remember this, because you don’t get that many victories in science,” he wrote to her.

The tweet from Bilbo came at the perfect time. “For someone like Staci, who has made it through to the other side and who is so successful,” Green shared, “a strong woman in science — to be interested in my work — it made me think: If Staci thinks I can do this, maybe I really can.”

Green immediately printed the tweet and wrote a note of encouragement to herself on the back, then pinned the keepsake to her workspace corkboard as a reminder to keep going.

Green felt seen by someone she truly admired, another woman in science making her way. After all, the glia community is a female-dominated field, due in great part to glial biology pioneer, Ben Barres, a transgender man who fought for women scientists’ visibility and equity. “He trained so many luminaries in the field,” Bilbo shared.

Like Barres, Bilbo wants to champion the work of other women scientists and the tweet about Green’s discovery was a no-brainer: “If you're further along in your career, you can have a big impact on someone who's just starting,” she said.

“For Lauren to leave science?” Bilbo thinks back, “It would have been awful. Her work is truly one of my favorite microglia papers ever.”

After the tweet, Green and Bilbo chatted over email and coordinated a visit to Duke with a Bilbo Lab postdoc role in mind.

It was a great fit and Green immediately felt at home.

“I loved the environment,” Green said. “Not just how Staci is as a scientist, but also the community that she and her lab mates have cultivated. It’s a very inviting, welcoming space of unique people that love science. And, also, Staci believes in me. I just knew this is where I'm supposed to be.”